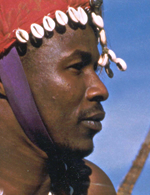

If you have been following the work of the Center for Traditional Music and Dance (CTMD), you probably know of Sidiki Conde, the dancer from Guinea and leader of the African music and dance troupe called Tokounou. If you have seen him perform, you won’t soon forget the marvel of his dancing on his hands. What you may not know is that Sidiki is also a highly accomplished musician, singer and an international leader in the movement to empower the disabled in the US and in Africa. In September of 2007, Sidiki added a new honor to his growing collection —he was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship by the National Endowment of the Arts, the federal governmentís highest award for tradition-based artists.

I first met Sidiki in 1998, when he came to New York from his native land of Guinea, West Africa to join the troupe Les Merveilles de Guinée. This company, first presented by CTMD at its Folk Parks festival in 1996, was then called Les Merveilles d’Afrique, and was led by the inspirational choreographer Kemoko Sano. Mr. Sano had directed the national dance company of Guinea, Les Ballets Africains, during the 1980s and early 1990s.

Sano frequently toured Guinea to recruit talented young musicians and dancers. He also sought to bring into the company members with unusual abilities. Sano wanted the troupe to demonstrate that music and dance is something for all people, including those who have overcome seemingly insurmountable obstacles to realize the dream of performing. This was how Sano met Sidiki.

Sidiki was one of 35 children of Ibrahima Conde, a military officer trained in France who returned to serve Guinea during the period of independence in 1958. Sidiki grew up in the Eastern region of Guinea, near the town of Kan Kan on the border of Mali. At the age of fourteen, Sidiki contracted polio and lost the use of his legs. As such a disability was traditionally seen in Guinea as a sign of bad luck for a family, he was sent away to be raised by his grandfather and uncle. Through sheer determination, Sidiki resolved to overcome his disability and prove he could excel in a world seemingly closed to him — African dance. He built up his upper body strength to the point of gaining mobility equal to that of a person with working legs. But then he would prove that he could do even more.

Sidiki rapidly rose in Sano’s second dance company, and in 1988 he became the rehearsal master. In this position, he was responsible for the organization of the company’s training regimen. He also developed a natural ability for choreography and all of the skills and patience required to keep a troupe of up to twenty often unpredictable artists in line and ready to perform under some of the most trying conditions. During the early 1990s the troupe toured Mali and Nigeria in West Africa, as well as Europe and Australia. In 1996, Sano brought the company to New York for a collaborative performance program with the Vanguard Jazz Orchestra. Once Sano’s company was established in New York, he sent for Sidiki in 1998.

Sidiki rejoined the company and assumed his former role, but in 1999, he also established his own company, the Tokounou All-Abilities Dance and Music Ensemble. This is a dance troupe which celebrates the ability of music and dance to transcend challenges, whether they are physical disabilities or the inability for people of different cultures to communicate with each other. Sidiki worked extensively with children and adults of all abilities giving performances while teaching African dance and music in schools, hospitals and universities. His projects have included performances and artistic residencies with Tokounou in a variety of New York City public schools that serve youth with disabilities. He volunteered as a choreographer with National Dance Institute’s children’s mixed ability dance program and worked in Connecticut to develop a mixed ability dance program, Bridging the Gap. In June 2000 and in June 2007, Conde was a featured performer in danceAble, part of Dance Florida.

In May of 2000, Sidiki branched out into the world of sports and hand-cycled across America for twenty-two days as part of World TEAM (The Exceptional Athlete Matters) Sport’s Face of America athletic and humanitarian event. He served as a member of the eventís Speaker Bureau, traveling throughout the northeast as a motivational speaker. In 2002, Sidiki and Tokounou were featured performers in the International Festival for Different Abilities in Carpi, Italy and they were invited back in 2008. And since its founding, Tokounou has been a featured company in the Center for Traditional Music and Dance’s Touring Artists program.

Through all this success in the US, Sidiki never lost sight of his roots and obligations to his family in Guinea. Since gaining a green card, Sidiki has been able to return to Guinea, bringing support for his family and working toward the dream of establishing a school for the disabled in Conakry. In 2004, he returned to Guinea with a film crew to document his journey back to the forested region of his home village near Kan Kan, where he is something of a legend.

To visit Sidiki, you have to go to the apartment he shares with his wife, visual artist Deborah Ross, on the Lower East Side of Manhattan. The first thing that strikes a visitor is the sight of his wheel chair parked inside the building lobby door. Climbing the five flights of stairs up to the top floor, one realizes the amazing strength of this man, able to climb up and down this Manhattan mountainside using only his hands.

One Tuesday morning in mid-November, Sidiki sat at ease on the couch by the window in the small apartment, having his morning cigarette by the window. He was in a good mood, seemingly surprised and yet pleased with each contact with the world. Deborah Ross, who also serves as his representative and manager, was there. She has worked tirelessly to support Sidiki in his artistic expression, the organization of his dance company and his humanitarian work. We were soon joined by Sekou Dembele, the lead djembe drummer in Tokounou. We talked about the many projects that Sidiki has been involved with, from performance to teaching to advocacy and now his National Heritage Fellowship.

In addition to his performance and teaching, Sidiki recently had the opportunity to visit Bahia in Brazil with support of a travel grant from the Jerome Foundation. He was able to connect with masters of the capoeira and candomblé traditions, and immediately made the cultural connections with Africa. Describing his experience, he said: “The culture is so good. There is culture there from the Yoruba in Nigeria and from Ghana. That is what they are using. It is an amazing thing.”

He described being able to speak Yoruba words during the Orisha ceremonies, having learned Yoruba “when we traveled to Nigeria with Les Merveilles de Guinée. So they have some music in capoeira. I heard that and I said, ‘Oh, I know that music.’ I heard some of the music from the Susu people in Kandia [Guinea], Abou Sylla’s people. That was so great. So we did some dance together and we did a show.”

Among the subjects that dominated the discussion were Sidiki’s and Deborah’s trip to Guinea in 2004 and the video documentary that is emerging from that trip. During this trip, Sidiki was able to reconnect with his family and members of his first band, Message D’Espoir (“Message of Hope”), with whom he performed in the mid-1980s and was first able to transcend the barriers of disability to show fellow Africans that people can contribute meaningfully to their communities and cultures regardless of their condition and abilities.

Describing his village, he said: “It is near the town of Tokounou. That is why my band is called Tokounou. Tokounou is the capital of the region of my home village. After then, we had the idea of making a film. Maybe it will be a little bit about what I am learning and what I want to do. I don’t work just because I want to work. I work for a reason. That is the why I am here.”

More specifically, his goal is to establish a school for the physically challenged in Conakry, Guinea. “Music and dance are there,” he continued, “but I just want to teach others to be independent in life and learning. We will teach them how to live life to be independent, so that they donít think ‘Oh [someone] is coming so how can we get him to give us five dollars.’ No, you have to learn how to look for this five dollars for yourself. They will learn how to make their clothes, and learn how to be more responsible for themselves. They will learn reading and writing. They will learn wheelchair basketball. But we have come some way now. We have more of a normal life. We have some jobs, and get married now.”

Sidiki hopes the National Heritage Fellowship will help him gain recognition and raise the funds to establish the school in Guinea, achieving his dream of bridging his old life in Guinea and his new one in New York. In this effort, Sidiki is a true international leader in promoting intercultural understanding and developing opportunities for the disabled.