Over the past three months, the New York klezmer scene lost two leading old-time clarinetists/band leaders. Marty Levitt and Rudy Tepel were both active during a period when klezmer music declined in popularity amongst the mainstream American Jewish community, though demand grew within Hasidic circles. I interviewed Professor Joel Rubin of the University of Virginia, an ethnomusicologist and leading klezmer clarinetist and scholar, for background about Levitt and Tepel. Through his research, Rubin had come to know both men well.

Though Rudy Tepel was the older of the two musicians, Marty Levitt was in many ways more representative of the previous generation of klezmorim. The Levitt family, along with a small number of other families such as the Beckermans, Kutchers, Farbermans and Brandweins, represented the major klezmer dynasties in New York.

Marty’s grandfather was a violinist named Levinsky, whose sons Lou Levinn, and Frank, Phil and Jack Levitt carried on the family trade. Lou and Frank were well-known trumpeters. While Lou was regarded as the leading Jewish trumpet virtuoso of his generation and played and recorded often with clarinetist Dave Tarras, Frank actually had a reputation as a better Jewish stylist. Marty’s father Jack was a multi-instrumentalist who played trombone with leading ensembles such as Cherniavsky’s Orchestra and the Boiberiker Kapelye.

Marty Levitt was born in New York in 1930 and got his professional start in the late 1940s, working for violinist/band leader Abe Schwartz. With a wealth of talent in his own family to call on, Levitt early on made the leap to booking “club dates” (the New York musicians’ term for weddings and other events held in catering halls) under his own name. He would often hire his father and uncles as well as friends from other klezmer families such as trombonist Sammy Kutcher.

Levitt found a niche playing for more recent immigrants who had survived the Holocaust. The survivors, often referred to derisively as “grine” (“green,” as in “greenhorns” who were only recently off the boat), favored coterritorial Polish and Russian repertoire as well as cosmopolitan repertoire such as tangos and waltzes. Levitt’s mother taught his wife, Harriet Kane, to sing with the band in Russian and Polish, and Marty was known as the “Tango King.”

Levitt did not have a reputation as a great jazz player, and this probably limited his ability to penetrate the wider Jewish club date market. However, his bands remained popular amongst the landsmanshaftn, mutual aid societies organized by Jews emigrating from the same town, as he could draw upon a huge repertoire of freylekhs, shers and other Jewish material, much of which had been collected and transcribed by his father. As Levitt related to Rubin in an 1990 interview:

“What was unique about me is that I was the only one in my age group that knew that repertoire, because my father was somehow under the idea that if you learned that repertoire, you’ll always make a living. But he didn’t realize the migration had stopped and when I was set to go there was no one around to play it for.”

Unlike Levitt, Rudy Tepel (born Harry Teplitsky ca. 1917) was not from a klezmer family. In fact, he got his start playing Dixieland and Swing, and began playing New York Jewish club dates because he was tired of touring on the big band circuit.

Tepel soon became associated with some members of the Brandwein clan, trumpeter Eddie Brandwein and drummer Murray Brandwein, both great-nephews of the Galician-born clarinetist Naftule Brandwein, whose recordings as a soloist continue to be revered by klezmer revivalists today along with those of Dave Tarras.

Tepel later met pianist Joe King, who was the first band leader to focus on serving orthodox communities such as Young Israel and the Hasidic movement. The Hasidic population in the Williamsburg, Crown Heights and Boro Park areas of Brooklyn was growing rapidly after release from Displaced Persons (D.P.) camps in Europe at the end of the 1940s.

Success in competing for Hasidic simkhes (celebrations such as weddings and bar mitzvahs) requires knowing the repertoire favored by each sect and gaining the favor of the sect’s leader, known as the rebbe. Like King, Tepel was orthodox but not Hasidic, but his experience in King’s ensemble enabled him to lead his own Hasidic band by the 1950s.

Tepel’s band would soon dominate the Hasidic/orthodox club date market. With his wife Lucille doing the booking, it was not uncommon for seven jobs to be booked on a Tuesday night employing dozens of musicians (Tuesdays are popular evenings for orthodox weddings, because the phrase “… and God saw that it was good” appears twice in the book of Genesis in reference to the creation of the third day—hence a Tuesday wedding is considered a harbinger of good luck for the newlyweds).

Longtime associate and saxophonist Howie Leess remembered Tepel as the leader who “had the best bands.” The Tepel lineup included regulars such as his former employer Joe King on piano, Moe Begun, Danny Rubinstein or Leess on clarinet and saxophone, and Eddie and Murray Brandwein on trumpet and drums respectively. During this period, Tepel’s main competition for Hasidic business was the Epstein Brothers’ band (featuring Max, Chi, Willie and Julie Epstein), though there was much overlap in personnel. Tepel also had a reputation for toughness; he practiced karate and was frequently known to carry a pistol with him to engagements.

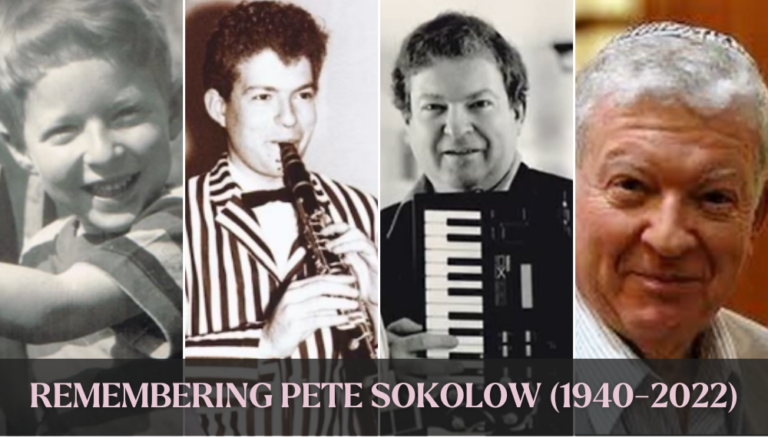

Tepel’s band remained popular into the 1970s, when newer rock-influenced bands like Mark III and the Neginah and Neshoma Orchestras pushed out the older ensembles. Tepel himself began to play with Neginah, and became known to klezmer revivalists as the original clarinetist of Klezmer Plus!, an ensemble founded in 1982 by banjoist/klezmer revival pioneer Henry Sapoznik and pianist Pete Sokolow in 1982 to perform the older New York club date repertoire (Tepel was later replaced in Klezmer Plus! by Sid Beckerman). In later years, Tepel would come back to jazz, playing at venues such as the Concord Hotel in the Catskills.

Both Levitt and Tepel are survived by children in the music field as well as their recordings. Marty’s son David is an accomplished jazz and klezmer trombonist, who was tutored by Sammy Kutcher. Marty’s albums “King of the Klezmers” and “Klezmer Weddings,” which feature wonderfully idiosyncratic arrangements and clarinet playing, are now available on CD. Rudy’s son Neil helped his father rerelease three classic Westminster recordings on CD, “Chassidic Wedding,” “Lubavitcher Wedding,” and “Bobover Wedding,” all wonderful documents of Hasidic repertoire and the Hasidic club date sound.

Links

For more information about purchasing Marty Levitt’s recordings

For Rudy Tepel’s recordings

For more information about University of Virginia Professor Joel Rubin